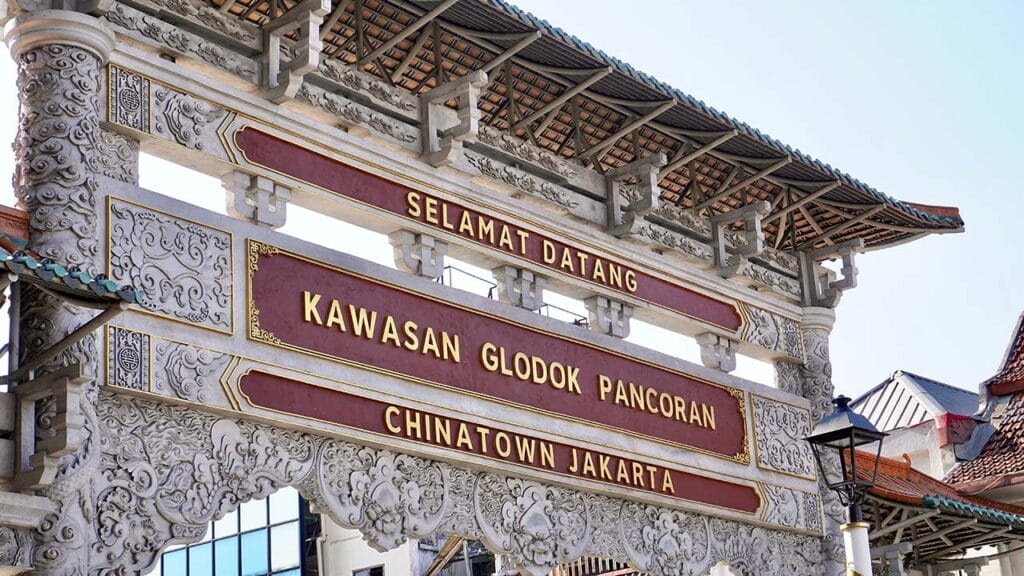

To step through the ornate paifang gate on Jalan Pancoran is to cross an invisible threshold into another Jakarta. Here, in Glodok, the air itself changes. The ubiquitous scent of the city’s traffic exhaust battles for dominance with thick, fragrant clouds of incense wafting from ancient temples and the tantalizing aroma of street food sizzling in woks. The sounds shift from the broad avenues’ roar to a more intimate cacophony: the chatter of vendors in a mix of Indonesian and Hokkien, the clatter of mahjong tiles from unseen rooms, and the persistent buzz of motorbikes navigating impossibly narrow alleys. Visually, it is a district of profound contrasts, where vibrant red lanterns dangle over storefronts packed with the latest electronics, and colonial-era shophouses with peeling paint stand in the shadow of modern shopping malls.

This is Glodok, Indonesia’s largest and oldest Chinatown, a district that is far more than a mere ethnic enclave. It is a living museum, a testament to the enduring, often embattled, spirit of the Chinese-Indonesian community. Its very existence is a story of fire and rebirth, of faith preserved against all odds, and of flavors passed down through generations. To walk its streets is to trace a history of tragedy and resilience, a narrative that is essential to understanding the multicultural soul of Jakarta itself.

The Crucible of History – A Chinatown Born of Bloodshed

The story of Glodok is inextricably linked to the history of Jakarta, then known as Batavia. It is a narrative that begins not in Glodok itself, but with the arrival of Chinese migrants who would shape the city’s destiny long before this district was conceived.

The Seeds of Settlement

From the 17th century, Chinese immigrants, primarily from the southern provinces of Fujian and Guangdong, arrived in Batavia as traders, artisans, and manual laborers. They quickly became indispensable to the Dutch East India Company (VOC), playing a pivotal role in the city’s economic life. They established vast sugar plantations, which became the cornerstone of Batavia’s primary exports of sugar and its potent byproduct, arak. As the city prospered, so did its Chinese population, which swelled from 3,101 in 1682 to a formidable 10,574 by 1739, a figure that began to alarm the colonial authorities.

The 1740 Geger Pecinan (Chinese Massacre)

The growing economic influence and population of the Chinese community fostered deep-seated anxiety within the VOC, which responded with increasingly restrictive regulations. Tensions reached a breaking point when a global surplus caused the price of sugar to plummet. This economic shockwave left thousands of Chinese coolies jobless, fueling widespread unrest and ultimately a rebellion. On October 9, 1740, the VOC’s fear erupted into unimaginable violence. In a brutal crackdown that would become known as the Geger Pecinan, Dutch forces massacred more than 10,000 ethnic Chinese and razed their settlement, which was then located north of modern-day Glodok in the Kali Besar area.

The Ghettoization and Rebirth

In the aftermath of the bloodbath, the VOC enacted a policy of strict segregation. In November 1740, the Dutch designated a new, contained area outside the city walls as the mandatory residential zone for the surviving Chinese population. This act of forced ghettoization was the birth of Glodok. The district’s physical form—a dense, labyrinthine network of narrow alleys and tightly packed shophouses—is a direct spatial legacy of this confinement. Forced into close quarters, the community developed a powerful sense of self-reliance and solidarity that would prove essential for its survival. From the ashes of tragedy, Glodok transformed itself into a bustling commercial and cultural hub, the resilient heart of Chinese life in Batavia.

A Cycle of Turmoil and Resilience

The 1740 massacre was not an isolated event but the beginning of a recurring pattern of persecution. Glodok was targeted again during the violent anti-communist purges of 1965 and, most notoriously, during the May 1998 riots that preceded the fall of President Soeharto. These events left deep physical and psychological scars on the community; some of the charred, abandoned buildings from 1998 still stand as silent monuments to that trauma. The Soeharto era (1966-1998) brought a more insidious form of suppression, with policies that forbade the use of Chinese names and the public expression of Chinese culture. It was during this period that historic temples were forced to adopt Indonesian-sounding names, such as the renaming of the ancient Kim Tek Ie temple to Vihara Dharma Bhakti.

A pivotal turning point came in 2000, when President Abdurrahman Wahid, affectionately known as Gus Dur, lifted these discriminatory restrictions. This act unleashed a cultural renaissance in Glodok. The vibrant, public celebrations of Chinese New Year and Cap Go Meh that now define the district are not the continuation of an unbroken tradition. Rather, they are a powerful and recent reclamation of a public identity that was suppressed for over three decades, making them profound statements of cultural and political re-emergence.

Sanctuaries of the Soul – The Spiritual Anchors of Glodok

Amidst the commercial clamor of Glodok, a network of temples and churches provides spiritual sanctuary and serves as the community’s cultural anchor. These are not static monuments but living spaces where centuries-old belief systems are practiced daily, connecting the present to a long and complex past.

The Heart of the Community: Vihara Dharma Bhakti (Jin De Yuan)

At the spiritual core of Glodok lies Vihara Dharma Bhakti, the oldest Chinese temple in Jakarta. Founded in 1650 by a Chinese lieutenant named Kwee Hoen, it was originally called Koan Im Teng and dedicated to Kwan Im, the goddess of mercy. The temple was a casualty of the 1740 massacre, burned to the ground before being rebuilt in 1755 by Chinese captain Oei Tjhie, who renamed it Kim Tek Ie (Jin De Yuan in Mandarin), meaning “Golden Wisdom”. Its current name, Vihara Dharma Bhakti, is a legacy of the Soeharto era’s assimilation policy.

The temple is an overwhelming sensory experience. Its bold red façade is adorned with intricately carved dragon motifs, while four great red pillars support its traditional roof. The air is perpetually thick with smoke from the thousands of joss sticks planted by devotees in a large bronze incense receptacle, or Hio-louw, as they pray for prosperity, health, and good fortune.

A Tapestry of Faiths

Beyond its oldest temple, Glodok is home to a diverse collection of religious sites that reflect the multifaceted spiritual life of its community.

- Vihara Dharma Jaya Toasebio: Founded in 1714, this prominent temple is visually striking with its vivid red walls and ornate altars. It embodies a syncretic faith, reflecting a harmonious blend of Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucian traditions.

- Other Temples: The area is dotted with other historic places of worship, including the Dharma Sakti Temple and Hui Tek Bio Temple, which form part of Glodok’s old religious heartland. Tucked away in residential alleys, the smaller Vihara Satya Dharma offers a more intimate glimpse into the daily faith of local residents.

- Santa Maria de Fatima Church: Perhaps the most compelling symbol of cultural fusion in Glodok is this Catholic church, built in 1850. Originally the residence of a wealthy Chinese captain, the building was later converted into a church but retained its distinct Chinese architectural style, complete with curved tiled roofs and red pillars. The existence of this structure is a profound testament to the community’s history of adaptation, demonstrating how new faiths could be embraced without abandoning cultural aesthetics. The very architecture of Glodok’s sacred spaces tells a story of negotiation—between faith and politics, tradition and assimilation.

A Gastronomic Pilgrimage – Tasting the Legacy of Generations

To understand Glodok is to taste it. The district’s culinary landscape is a rich tapestry woven from recipes passed down through generations, a fusion of Chinese provincial cooking and local Indonesian influences. Exploring its food scene is a journey through time, with legendary institutions standing alongside trendy new hotspots.

The Morning Ritual: Legendary Coffee and Heritage Tea

The day in Glodok properly begins with a choice of two iconic beverages. Tucked away in the legendary food alley of Gang Gloria is Kopi Es Tak Kie, a coffee shop that has been a community hub since 1927. Now run by the fourth generation of the founding family, this cherished spot has a down-to-earth, convivial atmosphere where patrons sit elbow-to-elbow. The menu is simple: black or milk coffee, made from robusta beans from Lampung, Sumatra. The undisputed star is the iced milk coffee, prepared Peranakan-style with condensed milk—a perfect antidote to Jakarta’s heat. Visitors are advised to arrive before 1 p.m., as the shop often runs out of coffee and closes for the day.

For a more refined start, there is the Pantjoran Tea House. Located at the gateway to Chinatown, it is housed in a beautifully restored two-story heritage building that was once a pharmacy dating back to 1928. With its elegant wooden screens and glowing red lanterns, it offers a serene atmosphere for a traditional dim sum breakfast, which is strictly a morning affair. Standout dishes include crystal shrimp dumplings (hakao), lotus leaf-wrapped glutinous rice (lo mai gai), and savory chicken feet.

The Alleys of Flavor: Navigating Gang Gloria and Petak Sembilan Market

Gang Gloria is the pulsating heart of Glodok’s traditional cuisine. This narrow alley is lined with food stalls that have achieved near-legendary status, serving signature dishes for decades. Here one can find authentic versions of sek ba (a rich, savory stew of pork offal in soy sauce), soto betawi (a creamy beef soup with coconut milk), and gado-gado (a mixed vegetable salad with peanut sauce).

Nearby, the Petak Sembilan Market is not just a place to buy groceries but also a culinary destination. Amidst stalls selling fresh sea cucumbers, live eels, and exotic snakeskin fruit, vendors offer a variety of snacks and dishes. This is one of the only places to find the rare and refreshing Rujak Shanghai Encim, a unique salad of boiled cuttlefish, radish, and water spinach, all doused in a sweet and savory red sauce with a sprinkle of peanuts.

The Modern Palate: New Hubs and Street-Side Treats

While steeped in tradition, Glodok’s food scene is not static. The “new kid on the block” is Petak Enam, a former 1960s department store that has been transformed into a trendy, “Insta-worthy” food court. Attracting a younger, hipper crowd, it offers a mix of halal and non-halal options in a lively, modern setting that still pays homage to the area’s heritage. A must-try snack here are the Taiwanese Power Puffs, filled with a choice of custard, matcha, or durian cream.

No culinary tour is complete without sampling the street snacks. Carts throughout Glodok sell kue ape, a unique pandan-flavored pancake with delightfully crispy edges and a soft, spongy center. While it has a playful local nickname, kue tetek (“breast cake”), due to its shape, the polite term to use is kue ape. For a final coffee fix, Djauw Coffee offers a unique experience with its Turkish-style sand coffee, where the brew is prepared in a pot nestled in hot sand.

The Pulse of Commerce – From Ancient Remedies to Digital Hubs

Glodok’s identity is fundamentally tied to commerce. For centuries, it has been a vital economic engine for Jakarta, and today its commercial landscape is a fascinating study in contrasts, where ancient traditions and modern technologies are sold side-by-side.

The Traditional Heartbeat: Pasar Glodok and Petak Sembilan

The traditional market, centered around the bustling artery of Petak Sembilan Market (also known as Pasar Kemenangan), is the cultural and commercial heartbeat of the community. This is a classic Southeast Asian wet market, a chaotic and vibrant maze of stalls overflowing with goods. Here, vendors sell a dizzying array of fresh vegetables, meats, and seafood—including more exotic fare like skinned frogs, turtles, and eels. The market is also the primary source for Chinese groceries and unique cultural items essential for religious life, such as prayer joss paper, incense sticks, and intricately hand-crafted red lanterns.

A key feature of this traditional economy are the long-standing traditional Chinese medicine shops, or apothecaries. These stores, often run by the same family for generations, offer a fascinating glimpse into centuries-old healing practices, their shelves lined with jars of dried seahorses, ginseng root, deer antler powder, and countless other herbs and remedies.

The Electronics Empire: Harco Glodok and the Digital Bazaar

Just a short walk from the ancient remedies of Petak Sembilan lies Glodok’s other commercial identity: a sprawling hub for electronics, one of the largest in Southeast Asia when combined with the contiguous Mangga Dua area. This modern bazaar is centered around a cluster of utilitarian, multi-story malls like Harco Glodok, Plaza Glodok, and LTC Glodok.

Inside these buildings, the atmosphere is gritty and functional. Thousands of small, crammed shops compete to sell every conceivable electronic item, from the latest mobile phones, laptops, and gaming consoles to home appliances, speakers, and CCTV systems. LTC Glodok even specializes in trade supplies like plumbing and electrical equipment for contractors. The area is famous for its affordable prices, which fuels a vigorous culture of bargaining. However, it is also notorious for both original and counterfeit goods, making it essential for buyers to be cautious and always check for official warranties. This duality is the essence of Glodok’s economy: a place where one can buy a remedy based on a thousand-year-old tradition in one alley and a bootleg video game in the next, embodying the complex negotiation between heritage and modernity.

The Rhythm of Celebration – Life in the Glow of Red Lanterns

Twice a year, the daily rhythm of commerce and worship in Glodok gives way to an explosion of color, sound, and festivity. The Lunar New Year celebrations are the cultural pinnacle of the year, transforming the entire district into a vibrant stage for traditions that are both ancient and uniquely Indonesian.

Imlek (Chinese New Year)

In the weeks leading up to Imlek, or the Lunar New Year, a festive energy electrifies Glodok. The markets become even more crowded as shoppers flock to buy auspicious red decorations, new clothes, and traditional treats. Stalls overflow with red paper lanterns and specialize in selling Kue Keranjang, a sticky, sweet glutinous rice cake also known as nián gāo, which symbolizes a “higher year”. On New Year’s Eve, families gather for reunion dinners and flock to the temples to pray for luck and happiness in the coming year. The streets come alive with the thunderous drumming and acrobatic spectacle of the Barongsai (lion dance), believed to ward off evil spirits and bring good fortune.

Cap Go Meh (The Lantern Festival)

The celebrations culminate on the 15th and final day of the New Year festivities with Cap Go Meh. The name is derived from the Hokkien dialect, literally meaning “the fifteenth night,” marking the first full moon of the new lunar year. In Glodok, the festival is marked by the grand Toa Pe Kong Carnival, a spectacular parade featuring lion and dragon dances, cultural performances, and ornate floats, or kio, carrying statues of deities from the area’s various temples.

Significantly, this festival has evolved into a powerful expression of a hybrid Chinese-Indonesian identity. The parade often includes elements of local Betawi culture, such as the giant ondel-ondel effigies and the boisterous tanjidor orchestra, performing alongside the Chinese dragons. This cultural fusion is also embodied in the festival’s signature dish, Lontong Cap Go Meh. This dish, a perfect example of Peranakan culinary assimilation, substitutes the traditional Chinese rice balls with Javanese lontong (compressed rice cakes), served in a rich coconut milk curry with chicken, soy-braised egg, and other Indonesian accompaniments. By incorporating local elements into their most sacred festival, the community performs a public act of bridge-building, celebrating an identity that is proudly both Chinese and Indonesian.

An Explorer’s Compendium – A Practical Guide to Glodok

Navigating Glodok’s vibrant chaos can be daunting for the first-time visitor. A little planning can transform the experience from overwhelming to unforgettable. This guide provides practical information for exploring the heart of Jakarta’s Chinatown.

Navigating the Labyrinth: Getting There and Around

Glodok is well-connected to Jakarta’s public transportation network. The most convenient options include:

- TransJakarta Bus: The busway’s Corridor 1 (Blok M – Kota) has a dedicated “Glodok” stop, placing you right at the district’s edge.

- KRL Commuter Line: Take the train to Jakarta Kota station. From there, Glodok is about a 10-15 minute walk to the south.

- From the Airport: A combination of the airport train to Manggarai station, followed by a commuter line train to Jakarta Kota, is an efficient option.

Once in Glodok, the best way to explore its dense network of alleys and markets is on foot. For longer distances within the area or for a more novel experience, cycle rickshaws are also available for hire.

Timing Your Visit

- Best Time of Day: Mornings are ideal. The markets are at their most lively between 7 a.m. and noon, offering the best atmosphere and the freshest goods. This is also the best time for a dim sum breakfast at Pantjoran Tea House or a coffee at Kopi Es Tak Kie before it closes.

- Best Time of Year: Jakarta’s dry season, from May to October, offers more comfortable weather for walking. However, for the most culturally immersive experience, plan your visit during the Chinese New Year (Imlek) in January or February, and especially for the Cap Go Meh festival 15 days later. Be prepared for massive crowds during this period.

A Curated One-Day Itinerary

- Morning (9:00 AM – 12:00 PM): Begin at the Pantjoran Tea House for a dim sum breakfast. Afterward, immerse yourself in the sights and sounds of the Petak Sembilan wet market before finding tranquility at the historic Vihara Dharma Bhakti.

- Lunch (12:00 PM – 1:30 PM): Dive into Gang Gloria for an authentic lunch at one of its legendary stalls. Cap it off with an iced coffee from Kopi Es Tak Kie.

- Afternoon (1:30 PM – 4:00 PM): Wander the alleys, visiting other temples like Vihara Toa Se Bio. Then, experience the district’s modern side by exploring the bustling electronics floors of Harco Glodok.

- Late Afternoon (4:00 PM onwards): Wind down at a modern spot. Grab a snack like the famous Taiwanese Power Puffs at Petak Enam or experience a unique sand coffee at Djauw Coffee.

Visitor Tips

- Wear comfortable walking shoes as you will be on your feet for hours.

- Be prepared for crowds, especially on weekends and during festivals.

- Carry small denominations of cash (Rupiah) for street food vendors and market stalls.

- When visiting temples, dress modestly and be respectful of worshippers.

- For Muslim visitors, be mindful when choosing food, as many dishes in Glodok are non-halal and contain pork.

The Unbreakable Spirit

Glodok is more than a destination; it is a narrative. It is a story of a community forged in the crucible of violence, that learned to thrive within the walls of segregation, and that preserved its culture against decades of suppression. Today, it stands as a powerful symbol of the Chinese-Indonesian experience—a microcosm of survival, adaptation, and syncretism within the sprawling metropolis of Jakarta.

To walk its narrow lanes is to witness this history firsthand. Every temple whispering prayers, every food stall serving a generational recipe, and every bustling market alley tells a piece of this story. Glodok’s spirit is not found in any single landmark but in the vibrant, chaotic, and enduring life that flows through its veins. It is a spirit of resilience that has proven, time and again, to be unbreakable.